“They say you mustn’t use [herb] because it make you rebel…against what?”

– Bob Marley

In just over a week, Californians will have the opportunity to approve the legalization of marijuana. Proposition 19 calls for the legalization, regulation and taxation of marijuana, in effect giving the marijuana the status of alcohol and tobacco in the state. If passed by the voters, the new law will not affect the U.S. federal laws, and it will probably be challenged in the courts. Nonetheless, the proposition remains popular, maintaining a small lead in the polls despite very little to no campaign advertising as of yet. The backers of the proposition are probably waiting to spend their money in the last weeks of the campaign season to push the proposition over the top. After all, U.S. elections, whether local or national, are very expensive, most of that money buying television time. The current Republican candidate for governor, Meg Whitman, has already set a record for money spent on her campaign with a month to go.

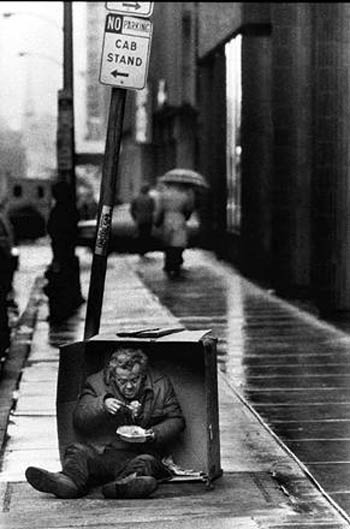

Governor Schwarzenegger, despite his opposition to Proposition 19, recently signed California Senate Bill 1449, reducing possession of an ounce or less of marijuana to an infraction. On Thursday, September 30, 2010, possession of an ounce or less of marijuana became punishable by the issuance of a $100 ticket. A court appearance is no longer necessary in California, and no criminal record will be generated. This is of the utmost importance for California’s African communities. Because California is a three-strikes State – three felony crimes and one is imprisoned for life – the compilation of a criminal record becomes a critical tool in pipelining African and Chicano-Mexicano youth into the prison industrial complex. So the reduction of possession of an ounce or less to an infraction is a progressive move against one of the more pernicious modalities of the police state, the War on Drugs.

Even so, the passage of Proposition 19 would be a more fundamentally significant move. Police agencies have already shown their willingness to ignore lenient marijuana policies. Pennsylvania, at least Philadelphia, has implemented a similar policy. There, in defiance of the new policy, the police still arrest Black youth and others, willing to waste the time and the resources of the court even though they know that the simple marijuana possession cases will be thrown out and the “offender” sent to drug intervention workshops. Also, in recent months, Los Angeles County Sheriff Lee Baca and Attorney General Steve Cooley, a current candidate for State Attorney General, have attacked the legality and safety of the county’s medical marijuana dispensaries. They claim that they are magnets for crime. And indeed they may attract some very specific crime. They do in fact collect thousands of dollars every day, a tempting target for larceny. When local dispensaries have been robbed, the thieves are after money. Furthermore, any herb they may take will still draw a nice sum on the streets. The illegal status of the herb continues to make it a lucrative commodity on the underground market. It is exactly its prohibition that attracts a real criminal element, much like the alcohol prohibition of the early Twentieth Century fueled the careers of some of the U.S.’s most notorious gangsters, like Al Capone. Legalization should result in better regulation of the dispensaries, as well as provide for better protection. Several observers and commentators in Mexico are hoping for the proposition’s passage, expecting legalization to have a ripple effect in their country, offering the currently warring drug cartels, police agencies and military a route to the peaceful regulation of the marijuana industry in their much suffering country. Marijuana is the number one cash crop of the Mexican cartels. It should also be noted that the hostilities in Mexico increased immediately after the Bush administration forced the Mexican government to reverse its decriminalization of marijuana within days of doing so back in 2006.

More than ten years after Californian voters approved legal access to medical marijuana, patients have been able to secure safe access to their medicine, and local neighborhoods no longer have to deal with mobile drug markets setting up shop in the streets, with cars slowly cruising by and young men and women running to car windows, nervously looking over their shoulders. Indeed, instead of relying on the underground economy for a livable income, these youth may have the opportunity to create work in a legal marijuana and hemp economy. As it stands now, even with the reduction of penalties to an infraction does not protect against prosecution for intent to sell charges or possession of more than an ounce, a necessary condition for those supplying the dispensaries. African and Chicano-Mexicano Californians disproportionately suffer prosecution for these kinds of drug charges.

The proposition has garnered widespread support. Former Surgeon-General of the United States Dr. Joycelyn Elders has co-written the rebuttal to the Argument against Proposition 19 in the official California voter information guide. Because of the possibilities for economic development and the emergence of a broader and regularized marijuana-hemp economy, several unions support Proposition 19, including agricultural workers and health workers. The proposition also enjoys the support of the California NAACP, the state Black Chamber of Commerce, several retired police chiefs and narcotics detectives, and the National Black Police Association (NBPA). Ronald Hampton, the director of the NBPA, explains that their organization supports the proposition in accordance with their commitment to reduced harm to Black people. As a retired police officer, Hampton has direct experience of the negative impact of the Drug War on African communities. He is also very aware of and vocal about the fundamentally antagonistic relationship U.S. police agencies have with the national U.S. African community. Proposition 19 removes a pretext for involving African and Chicano-Mexicano communities, and other colonized and working class communities, in the criminal injustice system in California.

Herb is the healing of the nation. Uniquely evolved to interact with the human brain, herb has played a role in human cultures for at least as long as the historic period. Extensive study for more than fifty years now has shown marijuana to be no more addictive than coffee is, and much less dangerous than alcohol or tobacco, both of which have privileged roles in the social and cultural life of Western societies. Like other areas of life, Western attitudes toward cultural practices defined outside the Western norm continue to minimize and criminalize what have been forms of living and healing and praying for thousands of years. Horace Campbell, quoting Dr. Lambos Comitas, calls this outlawing a popular custom, a convenient tool for social control. It is a critical aspect of colonialism, the colonizing of social rituals and the imposition of laws that again serve the interests of Western powers. So while industrialized countries like the United Kingdom invest in the development of hemp based industries, countries of the Global South are sites of hot wars and police actions in the Drug War when they are well suited to free themselves from Western dependency through the development of a crop that has multiple industrial, nutritional, medicinal, spiritual and recreational uses. Indeed, many in California are gearing up for an emergent marijuana tourism bump, much like Amsterdam.

There can be no doubt that within a capitalist economy, herb has become a fetish commodity. That is what capitalism does, turn things, people and ideas into commodities to be bought and sold. Even now, many in the world know nothing or very little of the revolutionary and nationalist character of Rastafari. For many, Bob Marley has been reconstructed as a kind of Jamaican hippy, a voice for freedom, peace, love and herb. Bob’s commitment to African unity, Black power, and revolutionary change has been muted. When these fans listen to “Kaya” they may appreciate the celebration of the Irie feeling, but do they know anything about burning a chalice to burn down Babylon? Do they know about the herb that Bob says that the Zimbabwe freedom fighters told him about, an herb that they said made them invisible to the enemy? We have to expect that a society founded on the exploitation of commodities will attempt to structure an industry that maintains uneven and unequal social relationships. Nevertheless, one reason less to embroil working class folks, African or otherwise, in the criminal injustice system is a positive development. Dr. Lester Grinspoon, Associate Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, in the late 1960s did a study of marijuana because, he says, he wanted young people at the time to be more aware of the dangers associated with marijuana use. By the end of his study, he concluded that the greatest danger posed by marijuana is its illegal status. On November 2, Californian voters have a chance to change that in the most populous state in the U.S. I, for one, am hoping that we have the wisdom and insight to do so. Free the herb, and free I and I. If you’re in California, vote yes on Proposition 19. For more information, please visit www.cannabisplanet.tv and www.mpp.org.

![brazilian women black men love[1]](https://freeignace.blog/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/brazilian-women-black-men-love1.jpg?w=199&h=300)